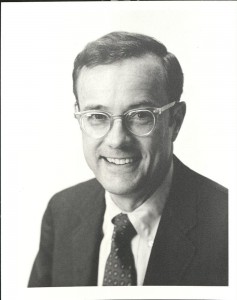

The following thoughts and photos were shared by Tim Murnane:

Bobby Coombs

2012

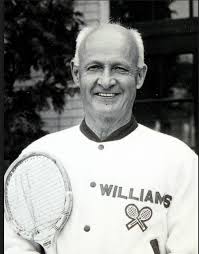

His 5 foot 9 inch, 160 pound frame was not what you would call “Major League.” His frequent appearances in scrimmages with his Williams College baseball squad usually resulted in an 0 for 4 for everyone and laughs of joy from the 60 something coach. He was the baseball man at Williams for almost thirty years. He was one of a kind, a character, an unforgettable man.

Raymond Franklin “Bobby” Coombs was, more than anything, a “Mainer.” Born in Goodwins Mills, ME in 1908, he spoke with a rich, northern New England accent and loved the ocean. He was a summertime fishing guide, chartering out of Perkins Cove in Ogunquit, ME, his offseason home.

To his players, Bobby was the coach, a friend and a mentor. He loved his players and relished being with them whether on the field, driving in school station wagons to away games or touring North Carolina for the annual spring training trip. Those two week trips, intended to get ready for the season in New England, required Bobby and his team to sleep in bunks at the visiting teams’ gym. Bobby was there with his boys every night, snoring away. He kept everyone awake, but, no one would wake him.

If asked about rules for his players, Bobby’s answer, always smiling, “Just one, no smokin’ on the bench.”

On away trips, when choosing a place for lunch, Bobby’s preference was always, in his perfect Maine dialect, “Let’s eat at the counta. It’s quicka.”

His ubiquitous corn cob pipe, which doubled, along with his scorebook, as a sign prop during games, might cause a stranger to misunderstand him. But, Bobby was not to be underestimated. A former Major Leaguer, graduate of Philipps Exeter Academy (after attending Kennebunk, ME High School) and Duke and a WWII veteran, Bobby was a man of intelligence, humor and humility. His words were thoughtful, straightforward and simple.

Bobby came from baseball royalty. His uncle, Jack Coombs, was a great Major League pitcher and longtime legendary baseball coach at Duke (1929-1952). Jack’s first college head coaching job was at, none other than, Williams from 1921-1924. Jack was a graduate of Colby College in Maine. The baseball fields at both Colby and Duke are named for him. He was a three time World Series champion and, in 1910 and 1911, won 31 and 28 games respectively for the Philadelphia Athletics.

Bobby became a legend himself in Maine and New Hampshire as a three sport high school phenom. In 1925 he struck out 26 batters in a nine inning high school no hitter.

He was an All American pitcher at Duke for Uncle Jack. He signed with the Philadelphia Athletics, Connie Mack’s team, after graduating in 1933. At age 25, on June 8,1933, he made his major league debut, entering a game against the Yankees in Philadelphia. The first batter he faced was Babe Ruth. The Babe took him deep, hitting one of the longest home runs of his illustrious career. Bobby would tell the story of that home run for his Williams boys over and over. It took him about a half hour to tell it, embellishing every detail, smiling all the while. He would leave out the fact that he retired Lou Gehrig and Tony Lazzeri to end the inning. He got his first Major League save that day

“Led the league in hittin’ in ’33,” Bobby would “brag.” “Went 2 for 5,” he would add with a wink (all true by the way).

After 21 appearances in 1933, Bobby told “Mr. Mack” that his arm was a little tired. He was immediately sent to the minors where he stayed for nearly ten years, playing in Syracuse, Birmingham, St. Paul, Shreveport and Jersey City, minor league cities for Boston, the Chicago White Sox, the Chicago Cubs and the New York Giants. He was called up to the Majors for another 9 appearance stint in 1943 with the Giants and then was released in June, 1943 at age 35. He joined the Navy where he spent two years and then came to Williams in 1946 to coach until his retirement in 1973.

During the spring of 1970, after the Kent State shootings, the occupation by students of the administration building at Williams and the early dismissal of the student body, Bobby faced a team of mostly liberal, determined and genuinely concerned players who told him they were not going to finish the season and were going home.

“Why would you do that?” Bobby asked. “We have games left. Why do you want to go home? I know you are upset, but this is baseball. Please don’t mix baseball and politics. Please take a couple of hours and come back and we’ll talk again.”

No one could really answer Bobby’s question and after an hour of gentle discussion, the team returned to Bobby’s office to tell him they would stay and finish the season. He was right and so were the players. And it turned out ok.

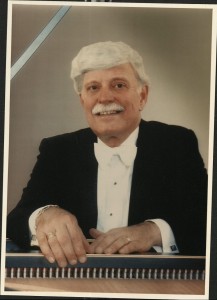

For those who knew, played for and loved Bobby Coombs, his greatest talent was being a beautiful human being; loving life, laughing, joking with his players, puffing on his pipe, enjoying the sea, recounting his appearance against the Babe.

Bobby has been gone since 1991. But, every spring, when the snow melts, players gather to get ready for the season and the grass gets green on Bobby Coombs field in Williamstown, Bobby comes to mind. He was a special man.

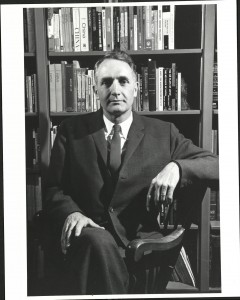

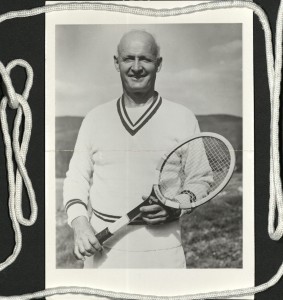

Bobby (left) at Duke in 1932 with Coach (and Uncle), Jack Coombs (center) and teammate Charles Herzog Jr.

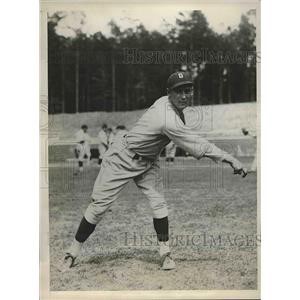

Bobby at Duke in 1933, his senior year:

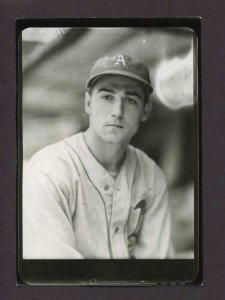

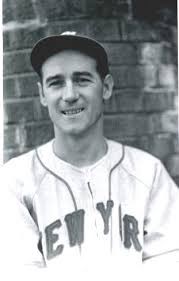

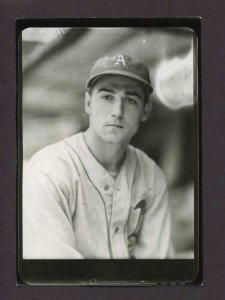

Bobby with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1933, his first season in the Major Leagues:

Bobby with the New York Giants in 1943, his last in the Majors: