|

|

|

ONE DATE – FLIPPING THE PERSPECTIVE

By Paul Lieberman

I’ve always found it useful, as a writer, to flip perspectives. One great feature of the computer age is how it allows us to do that with all sorts of episodes from the past, such as this prominent moment in our shared experience as members of the Williams class of ’71.

The date in question: Oct. 8, 1967, when Lady Bird Johnson came to Williamstown, setting off protests that made national news.

We were in school barely a month but had amply witnessed the passions inspired by the war in Vietnam. I’m pretty sure there already had been a gathering at Baxter Hall at which an anti-war football player – a FOOTBALL PLAYER – shouted, “I want action, action, action!” That also may have been when Prof. Robert Gaudino cautioned us children of privilege, “If you don’t go, who will?” meaning those less fortunate, of course.

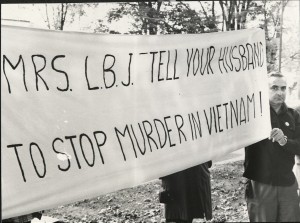

The First Lady’s presence at the fall Convocation had nothing to do with the war. She was invited to receive an honorary degree and help celebrate the opening of Williams’ pioneering Center for Environmental Studies. Yet the protesters were out when she was escorted into Chapin Hall by President Sawyer, one group with a banner urging her to tell her husband, “Stop Murder in Vietnam.”

A half century later, I’m not sure whether I sat in the back of Chapin or on the narrow balcony above. But I vividly remember being among a group of fellow freshmen who surprised me with their…let’s call it fervor. One of our classmates – no longer with us, sadly – had been emotional but level headed in late night political bull discussions in the dorms. When Lady Bird got up to speak, however, he seemed overtaken with rage as he booed and shouted out. At later protests in Washington, the popular chant was “Hey, hey LBJ, How many kids did you kill today?” I can’t remember what it was at Chapin but from our distant perch the First Lady seemed to be shaken, perhaps to tears, as dozens of students marched out of the hall. I was left shaken too, by the possessed look of that one classmate in particular. Passion for a cause was totally legitimate, of course, and a case could be made for making life uncomfortable for those behind policies leaving thousands dead and vast lands devastated. But his demeanor seemed to leave no room to ponder any thought, including very basic issues: Were these tactics effective? Might they even be counterproductive? Issues that resonate around protests to this day, of course.

Anyway, that was my perspective. The computer now shows us others.

Start with newsreel footage from outside and inside the hall.

Then a handwritten record of Lady Bird’s activities that day, to the minute.

Finally, the First Lady’s own thoughts, in her fleshed-out diary.

Read that, please. You’ll learn that she was well aware of the protesters … but also latched on to other signs outside Chapin, particularly one stating “MAY GOD GIVE LBJ STRENGTH TO CONTINUE HIS COURAGEOUS STAND ON THE PRESERVATION OF PEACE.”

Inside, she scanned the audience as we sang “America,” noticing that the front rows were filled with robed seniors.

“As I saw a white arm band on the first one, I was not prepared for it. I felt a quick pulse of emotion in my throat. I counted another and another. These were symbols of mourning for the war in Vietnam…

“When I was introduced, everyone rose, and it was at this point that some of the graduating class walked out….But the college had its own rebuttal….everybody standing so long and cheering so loudly that their departure was scarcely noticed and they must have felt rather flat. I was both touched and humbled by President Sawyer’s citation.”

From the podium, “I tried to look straight into the eyes of the students in front of me, and from one to another as the speech progressed, and I certainly spoke with passion if not expertise.”

Before and after the Chapin Hall turmoil, Lady Bird’s visit was removed from the public glare, putting her “far from the madding crowd,” she noted. Under the hosting of President Sawyer and Prof. James MacGregor Burns, a foremost scholar of the U.S. presidency, she was taken up to Mount Hope Farm to view the fall foliage, toured the Clark museum to see its Renoirs and bronzes, and was the guest of honor at a dinner at Williams’ version of the White House.

She concluded in her diary:

“How would I evaluate a day like this? Probably a mistake on balance, because what I had done is provide a vehicle for the dissenters, who were a minority, to get inches in the paper and minutes on the television screen…I was their bait—their creature—for the day.”

She had tried to praise a good cause, as she saw it, but “the louder voices of hate and anger shouted it down.”

“How did I personally feel as I walked among the picketers? Cool and firm and determined to maintain dignity. But through every pore, you sense sort of an animal passion right below the surface.”

“All in all, I guess I lost this round. Lyndon called—distressed—‘I just hate for you to have to take that sort of thing.’”

Perhaps, then, such protests contributed to Johnson’s eventual decision not to run for reelection, though chaos within the Democratic party would contribute to the election of Richard Nixon and the rest, as they say, is history.

Along the way, 11,363 Americans were killed in Vietnam by the end of 1967, 16,899 in 1968 and 11,780 in 1969, the deadliest period of a war that claimed 58,000 American casualties and many times more than that, of course, among the Vietnamese.

I really appreciate Paul Lieberman giving us a view of Lady Bird Johnson’s thoughts and feelings from her diary of October 8, 1967. That Convocation protest was the first I had ever witnessed. I didn’t know what to make of it all at the time, but my recollections of it color my memory. From the distance of over 50 years, and make me realize how much of a tragic feel I have for the Johnsons.