The question is as old as the origins of philosophical thought. “Can virtue be taught?” In a dialogue called the Meno, Socrates questions a young man named Meno concerning his definition of Virtue. According to Plato, after a series of frustrating questions, Meno throws up his hands saying that there is no way for the “ignorant to ever attain knowledge.” (Teaching With Your Mouth Shut, Donald Finkel p.34) In fact, Meno challenges Socrates entire approach to philosophical inquiry asking:

“How will you look for it, Socrates when you do not know what at all what it is? How will you aim to search for something you do not know at all? If you should meet it, how will you know that this is the thing that you did not know?”

It would appear that American education has answered Meno’s question with the resounding conclusion, “You can’t!” Except for a handful of independent schools large enough to offer departments and courses in religious, philosophical, and ethical studies and a few entrepreneurial, public school teachers who have found innovative ways to integrate ethical explorations into traditionally framed courses in history and social studies, a comprehensive approach to instruction in ethics and leadership is totally lacking in American schools today.

This is surprising given the fact that much of the early history of American schooling was grounded in an exploration of core virtues as the focus of elementary textbooks designed to teach students to read. “In early America, parents assumed a teacher would teach from a Christian perspective. Other than the Bible, the McGuffey Reader was the most read book in 1919. This popular text used biblical examples to teach character, morals and ethics. Instruction in morals, honesty, compassion, respect, and responsibility were taught.” (Historical Review of Ethics Education in America, Jimmilea Berryhill DPhil, Dlitt)

While there are clearly many reasons for the current absence of direct instruction in ethical discourse in schools, the drivers for this change would have to include the growing religious pluralism of American culture, the emergence of a more secular society, and the culture wars that have shaped social and political discourse since the 60’s. In short, the cultural common ground that made the teaching of ethics possible crumbled under the weight of diverging values, lifestyles, social roles, and religious beliefs. One can see this in the attempts made by teachers and curriculum writers during the past 40 years to find creative ways to maintain ethics as a curricular focus in the guise of “value neutral” programs like Values Clarification, Decision Making, Leadership Development, Civic Education, and Moral Reasoning .

It is interesting to note, however, that at the same time that the formal study of ethics began to disappear from the curricular landscape, progressive educators began to advocate for the inclusion of internship, service and leadership programs as a means of developing moral character and a sense of civic responsibility within students. The philosophical rationale for this approach finds its first expression in the work of Aristotle who “supposed that man became virtuous by doing the act itself rather than by pedagogical methods.” Echoing this theme, educational theorist R. J Nash in his book Answering the Virtuecrats (1997) “stated that true character showed through contact with others who served as mirrors to provide insightful glimpses of individual character in practice.” (Historical Review of Ethics Education in America, Jimmilea Berryhill DPhil, Dlitt).

Perhaps the most fully realized program of leadership development in the 20th century was developed by Kurt Hahn, the founder of the Gordonstoun School in Scotland during the 1920’s. Hahn believed that the development of leadership skills, personal courage, and civic responsibility could only be accomplished through an immersion in emotionally intense, physically challenging, and purposefully experiential learning experiences like sea rescue and firefighting training, outdoor challenge programs (think Outward Bound), and an educational community grounded in mutual service and personal responsibility.

For Hahn the road to leadership must afford every student “an intense experience surmounting challenges in a natural setting through which the individual builds his sense of self-worth, the group comes to a heightened awareness of the human interdependence, and all grow in concern for those in danger and in need.”(Outward Bound USA, Josh Miner p. 34) Today, national leadership programs like Outward Bound and the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS), as well as, numerous outdoor leadership academies throughout the United States including initiative/team building programs like Project Adventure, all have their philosophical and pedagogical roots in Hahn’s work.

For Hahn schools needed to promote a holistic approach to leadership development that was grounded in a challenging and rigorous approach to knowledge acquisition, inquiry and self-discovery, emotional and physical well-being, personal and social responsibility, empathy and compassion, social collaboration, and personal reflection.

For these goals to be meaningfully realized, Hahn believed it was essential that schools create real-world opportunities for students to serve their school and their community, to connect with and explore the natural world, to engage in inquiry-based, applied learning experiences, and to live and work within the context of highly interpersonal communities that upheld and fostered the highest standards of personal character and social responsibility.

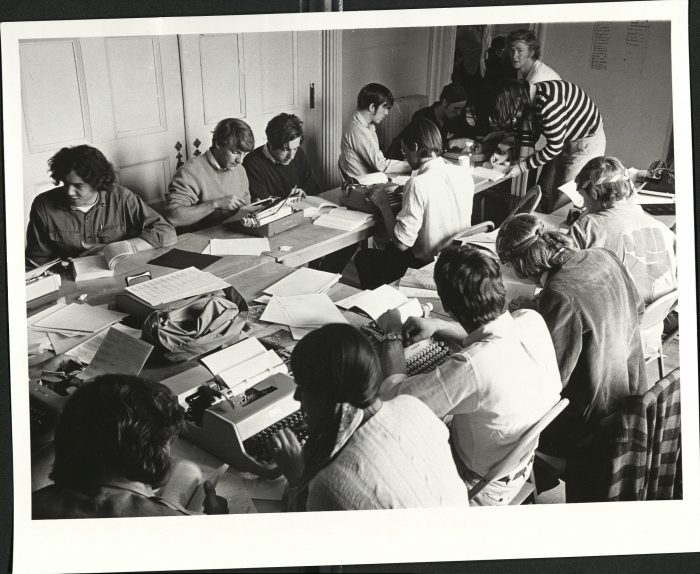

If all of this sounds a bit familiar, perhaps it is because during our years at Williams, Robert Guadino, Professor of Political Science from 1955 to 1974 inaugurated two transformational learning programs – Williams in India and Williams at Home. Guadino believed that, “It is strangers who have the most to teach us; we are assured by our loved ones, but we are taught by outsiders.” (Robert Guadino, “Silence is Suspect”) Up to the very end of his life, he continued to teach, mentor, and inspire his students, often holding classes in his home because he was too sick to get to his classroom.

Throughout his career, Gaudino argued that Williams should “actively promote a range of experiences that have the creative potential to unsettle and disturb” as part of a program of “uncomfortable learning” based on the “unsettling experience.” (Read source.)

“By challenging the notion that public, intellectual engagement should or could be divorced from the private realm of students’ personal background and experience, Gaudino required his students to confront uncomfortable differences and learn through contrasts – for example, between their assumptions and their conclusions, between themselves and others of different social, racial, and ethnic backgrounds, between modern and ancient thought, between the values of public institutions and those of the private home, and even between the different liberal arts disciplines themselves. With insight, discipline, and humor, Gaudino facilitated student confrontation of these contrasts both inside the classroom and outside Williams, in places as diverse as Iowa, India, Appalachia, and Detroit.” (Read source.)

In his short essay on teaching and learning, Silence is Suspect, Professor Guadino observed that, “{Higher levels of knowing} all involve encounters with difference. That is what they share, a brush with something or someone different. {Some feeling of} dislocation sets them apart {from the safety and security of one’s personal world-view}. {In varying degrees}, pain and discomfort are the {the essential roots} of an education – to be in touch with or in dialogue with difference, really up against it. The more varied the difference, the greater the possibility of being educated. Real education mistrusts what we are. It must, in order to be education… Success in pursuit of education is neither natural nor easy…. So, let us not confuse {a comfortable} education, with truly learning anything…”

It’s hard to imagine a fully realized 21st century education that does not fully engage students in the often uncomfortable and challenging process of engaging in difficult and often contentious ethical discourse with others, of compassionately confronting the diversity of the lived experience that defines each of us.

In my final years in the classroom, my students passionately wanted to explore together essential and enduring questions like:

➢ Where do our moral values come from? Are values universal and unchanging, embedded in the very fabric of existence, or are they the subjective constructs of human thought, defined and shaped entirely by their cultural and historical context?

➢ What is the good life? What is right conduct? Is there an ultimate purpose/meaning to life? To what extent are our lives shaped by genetic and/or environmental factors or are human beings free to shape their own destinies? Why is the answer that each of us gives to these questions profoundly important to the present and future course of each of our lives?

➢ Should scientists be held accountable for how their research is applied? Is there any science not worth pursing because of how it might/could be used? Is science blind to moral and ethical judgment? Should science have a conscience?

➢ Is “Might” right? What are the obligations of the powerful or the “haves?” What is the duty of an individual to the community? What is the duty of the community to the individual?

➢ Are we in debt to anyone or anything for the bare fact of our existence? If so, what do we owe, to whom, or to what? And how should we pay?

➢ How should we define and pursue justice—is justice a relative or absolute quality? How do we make our political, social, and economic life reflect our deepest values?

➢ What are the characteristics of authentic leadership? What does society expect from its leaders? What role do ethics play in leadership? How do we judge whether our leader’s goals and actions are moral?

➢ What is transformational leadership? Can one person really make a difference? Are great leaders born or a product of their times?

Given the current trajectory of 21st century American political, economic, and social life, it is becoming increasingly clear that fostering within young people the capacity to engage in honest, ethical discourse must be a cornerstone of every school’s instructional program. Central to achieving that goal is giving students the opportunity to envision their future, to consider the implications and meaning of the systemic forces that are driving their lives forward.

Principled leadership in this context means giving students the opportunity to actively shape their future, not simply live through it. It is essential that we provide young people with an education that fully embraces the recognition that, “Human survivability and creating new concepts of civilization are inextricably linked.” (The Meaning of the 21st Century, James Martin, page 13)

If we are to prepare students to meet the challenges shaping their lives, then ethical, philosophical, and even religious study need to reclaim their rightful place in today’s high school curriculum – not to mention the central role that creative thought must play in every young person’s education.

America today requires school cultures that both demand of and foster within every student the capacity, “to follow what one believes to be the right course in the face of discomforts, hardships, dangers, mockery, boredom, skepticism, and impulses of the moment.” (Hahn) Schools need to be places where everyone is told from the start that they are “crew not passengers,” where the journey, however uncertain at times, is everything, and where the critical ingredient for success is the personal cultivation of courage, perseverance, and honesty.

In the end, a truly 21st century education must speak to the richness and complexity of the human spirit and the interpersonal/cultural bonds that make us truly human.